Field Notes 1: A Historian Goes Underground

Or, wandering through bogs with expensive equipment in the hope of doing better landscape history

It was an early morning in June ‘23 when my flight touched down in Dublin, and I was exhausted. Back in the US, I had just moved all of my stuff, and had spent the days prior to the flight in a completely empty apartment, trying to wrap up loose ends before vanishing overseas for nearly three long months. Between that apartment, the airport, and the timezone, I’d say I was fairly untethered from any real sense of geography and time as I found my way to Dublin Heuston to catch a train.

I first joined the Castles in Communities excavation project in 2022, encouraged by a colleague and my advisor to get some on-the-ground (in-the-ground?) experience of archaeological methods. I am not a trained archaeologist. I spent all of my undergraduate years and the majority of my master’s degree wrestling with purely textual evidence and writing very text-heavy papers. I certainly felt more at home in a large edition of Bede’s History than I did in the middle of a chart-heavy archaeological report.

However, my Ph.D. research had already veered towards questions of landscape change in early medieval middle Britain, and the fifth to eighth centuries are not particularly well-represented in texts (they don’t call it the Dark Ages lightly!). Working on the landscape required me to come to terms with the vast (and rapidly growing) body of archaeological literature, and it seemed like sitting in a trench was going to help me figure that out. It did.

When leading a discussion section as a teaching assistant, there’s a reason that so much of our work with undergraduates revolves around helping them read primary sources, rather than just telling them about it. You can hand someone the big book of primary source research, but they only learn to be careful and discerning by doing that research themselves, and in time, they learn to read against the grain. In the process, they also learn why we have centuries of historical theory and practice - not just idle words, but historians trying to figure out how to approach the same problems that the students find themselves mired in.

Seeing the work process which sat behind each archaeological report I read was invaluable. I saw a million choices: how to sample, where to dig, what becomes a feature or a context, what makes a layer. I saw good digging, and bad digging (I was, in particular, not very good at excavation). When I returned to my books in the autumn of ‘22, ahead of my comprehensive exams, I felt far better able to think about how the excavators in those reports had chosen to approach their sites.

So, when I arrived on-site to the small village of Ballintober in County Roscommon that morning in 2023, I was ready. I had passed my comprehensive exams, I had written a dissertation proposal. Rather than digging, I was going to be helping my friend Andrew, an archaeology graduate student and fellow medievalist. Andrew’s good at geophysical survey, the art of non-invasive investigation of what’s under the ground, and his research involved checking out a fair few ringforts with the aid of magnetometry and ground-penetrating radar. Given my own interest in landscape and survey methods, I leapt at the opportunity to join him, and spent many days tramping over boggy ground in search of the invisible.

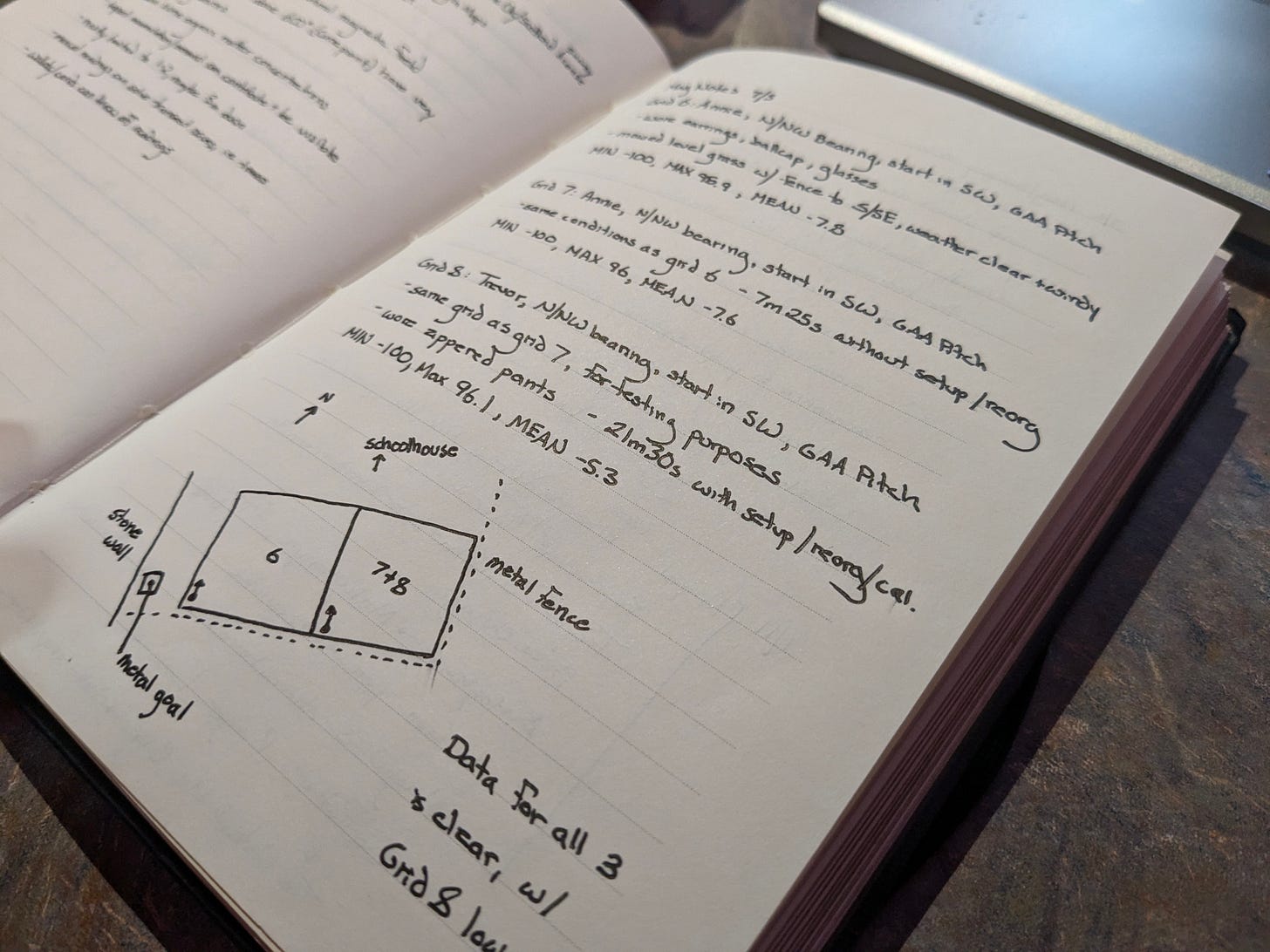

One thing that immediately became clear was the vast amount of information such surveys generated. I was rapidly placed in charge of guiding undergraduates through the basics of magnetometry alongside another team member, and we taught the students how to take prodigious notes about the survey conditions. Weather? Cattle in the field? Who’s on the team that day, and where did we lay the guide lines? My gridded notebook was filled with little observations and sketches. For a historian used to scraping over the same source material, the amount of raw data produced from a single day in the field was incredible.

It was also a thoroughly phenomenological experience. I stood with the team atop ringforts and scanned the horizon, looking for other sites that might have been intervisible. We sat in bogs, sheltering our equipment as rain pelted down over us, and we rejoiced when we finally tromped into our home base, the village schoolhouse, and clustered around the peat fire. Our luxuries, in many ways, took us far from our medieval subjects, but the smell and warmth of the peat, the diagonal sheets of rain, and the geography of the ringforts did seem to lessen the space between us and them, if only a little.

Here in 2024, looking back at those notes and photos, I’m struck by how interested I was on the landscape contexts of the sites we surveyed. I had written my dissertation proposal already by then - a proposal which has changed no small amount in the intervening year. A year on, and I’ve accumulated a surprisingly detailed map of sites, drawn from both the Scottish National Record of the Historic Environment (an incredible resource) and the many interesting excavation reports I’ve read. The map is filled with layers, attempts to capture some aspect of the landscape which others might leave out:

LiDAR maps from the National Library of Scotland showing the rise and fall of hills and plains

Georeferenced copies of the Roy maps (also from the NLS), drawn in the years following the Jacobite Rebellion and showing the extent of pre-industrial agriculture (a suggestion made for early medieval research by Leslie Alcock in his excellent survey)

Waterway data, showing all the little burns and streams and rivers which cross the areas around the Firths of Tay, Forth, and Clyde

Amidst these sit a multitude of little points: long-cist cemeteries and barrow burials, crop-marks of ancient souterrains and field boundaries, hillforts and carved stones, place-names and dig sites. I’ve already been pulling them together into cohesive landscapes, areas where I can talk about the transition between the Roman world and what came after, and I’m excited to finish up this chapter sooner rather than later.

Spending time in the fields of Co. Roscommon taught me a few things about how to build this map, and informed the research I’ve done using it since. I learned to keep a keen eye to the landscape context, to read the fuzzy data coming out of magnetometer or ground-penetrating radar, and that spending time on a site is invaluable - lessons I would bring with me in the following month when I traveled to Scotland and England. It taught me to stick with smart people, scholars of many disciplines who all bring unique approaches to the table, and to always remind myself to be humble when it came to exploring another discipline’s evidence.

I don’t want to finish this post with a grand imperative for historians to seek out excavations. I was beyond fortunate to be able to work at Ballintober for two summers, supported by university funding and brilliant colleagues. Field schools can be expensive, prohibitively so, and scary to those of us with no experience. But working with professional archaeologists helped me learn a lot, and changed my relationship not only with the excavation reports I read, but also with my historical texts. Excavations are happening everywhere, in Europe, in the US. If you get a chance to visit one and watch for a bit, I’d recommend taking it, if only to think about our history from a slightly different angle.

Bibliography, Used and Recommended

Some early medieval Scotland/Britain readings in the vein of this post

Leslie Alcock, Kings and Warriors, Craftsmen and Priests in Northern Britain, AD 550-850 (Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 2003).

Robin Fleming, The Material Fall of Roman Britain, 300-525 CE (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021).

James E. Fraser, From Caledonia to Pictland: Scotland to 795, The New Edinburgh History of Scotland 1 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009).

Adrián Maldonado, “Materialising the Afterlife: The Long Cist in Early Medieval Scotland,” in Creating Material Worlds: The Uses of Identity in Archaeology (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2016), 39–62.

Adrián Maldonado, “Burial in Early Medieval Scotland: New Questions,” Medieval Archaeology 57, no. 1 (2013): 1–34.

SESARF 2023 ‘Early Medieval’ Maldonado, Adrián and Cartwright, Rachel (ed.), Scottish Archaeological Research Framework: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Available online at https://scarf.scot/regional/sesarf/8-early-medieval/.

What I was recommended to learn geophysical survey

Kenneth Kvamme, “Magetometry: Nature’s Gift to Archaeology,” in Remote Sensing in Archaeology (University of Alabama Press, 2007), 205-233.

Jörg W.E. Fassbinder, “Seeing Beneath the Farmland, Steppe and Desert Soil: Magnetic Prospecting and Soil Magnetism,” Journal of Archaeological Science 56 (2015): 85-95.

What changed the way I look at the landscape

Christopher Y. Tilley, A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths, and Monuments, Explorations in Anthropology (Oxford, UK ; Providence, R.I.: Berg, 1994).

Robert Macfarlane, The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot (New York: Penguin Press, 2012)

A. Asa Eger, The Islamic-Byzantine Frontier: Interaction and Exchange Among Muslim and Christian Communities (London: I.B. Tauris & Co., 2017).

Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1991).

Excellent read. Might some of your readers benefit from you recommending a book or two specific to early medieval Ireland. One thing Ireland has over Scotland as you know is the that texts do exist. Thanks for publishing this Neil